Guidance for supporting the mental health of Afghan asylum seekers and refugees

This resource is directed towards professionals or volunteers that will come into contact with the Afghan refugee population and is intended to help you support the mental health and wellbeing of those refugees.

This resource is directed towards professionals or volunteers that will come into contact with the Afghan refugee population and is intended to help you support the mental health and wellbeing of those refugees.

Toolkit

Introduction

This resource is directed towards professionals or volunteers that will come into contact with the Afghan refugee population and is intended to help you support the mental health and wellbeing of those refugees.

Overview

On 15th August 2021, a 20-year war between Afghan and allied forces and the Taliban was brought to an end as the Taliban captured the country’s capital, Kabul and claimed victory. In a war that has claimed 241,000 lives since its beginning in 2001, 71,000 of these being civilian lives, it is important to acknowledge that a return to the oppressive Taliban regime will have severe mental health consequences, not only for those immediately caught up in the conflict and fleeing the country for reasons of safety but equally for the Afghan population in the U.K and London, whereby the risk of re-traumatisation is high and fears for their home country or friends and relatives still living there will be widespread.

A significant portion of Afghan migrants in London fled their native country as refugees escaping from the Taliban regime many years ago, therefore the news that they have taken back power will likely provoke feelings of stress and depression. It is well understood that rates of mental illness within refugee and migrant populations significantly exceed levels seen in the general population, therefore safeguarding and specialised, culturally competent support is required to ensure that the impact of this development in global affairs on mental health for these groups is managed.

Aim and scope

This resource is directed towards professionals or volunteers that will come into contact with the Afghan refugee population and is intended to help you support the mental health and wellbeing of those refugees.

While not at all comprehensive, we hope to lay a framework for engagement and promote shared learning across the system. This resource is a complement to the Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) Directory for Refugees and Migrants in London produced by the Centre for Society of Mental Health at Kings College London.

This work is part of the wider response to the UK Government and Mayor of London’s commitments arising from the humanitarian crisis caused by the recent withdrawal of ISAF forces from Afghanistan and resulting flow of Afghan refugees into the UK. We are keen to complement and not duplicate good initiatives already taking place.

The mental health of Afghan migrants and refugees

It is a well understood phenomenon that those displaced or fleeing their own country suffer from a higher prevalence of overall psychological distress and associated mental health conditions, PTSD and depression being the two most common. Trauma often occurs both pre- and post-migration, as an individual is exposed to traumatic conditions and situations that often form the catalyst for their departure, but equally after they arrive in a new country whereby language barriers, cultural barriers, marginalisation, and a loss of identity and belonging present further mental health challenges. Furthermore, legislative barriers and challenges to immigration can add to the trauma these refugees experience.

There is plenty of anecdotal evidence to suggest that the recapture of power by the Taliban in the country is a cause for great concern for Afghans living in the capital. Many Afghan immigrants fled their home country and moved to the U.K as a result of the Taliban regime and its associated oppression of society and numerous human rights violations, therefore there is a tangible risk of re-traumatisation of this group as a result of mere exposure to headlines and details on the situation.

It is well documented that mere awareness of a troubling or traumatic situation can reactivate past trauma and given the low uptake of mental health support such as counselling and therapy that has historically been the case in migrant groups, it is less likely that the underlying issues and sources of trauma will have been successfully confronted and treated, meaning that individuals’ resilience to negative reporting on the new Taliban regime will be massively diminished.

Trauma-Informed principles when engaging with the Afghan community

As these refugees and asylum seekers can have complex health needs and are likely to have undergone significant trauma, it is essential that all professionals who come into contact with them adopt a considered, trauma-informed approach.

This may be the first opportunity that a refugee has to talk about their needs and seek help. Therefore, we must create a culture of safety, support, and empowerment. A workforce that understands the impact of trauma does two things:

- Support the recovery by providing the person with a different experience of relationships.

- Promote safety over threat, choice over control, collaboration over coercion, and trust over betrayal.

- Reverse the association between trauma and relationships.

- Minimise the barriers to receiving care and support.

- Minimises potential triggers that will harm the individual.

- Empower the person to have control over their own care and encourage informed decision-making.

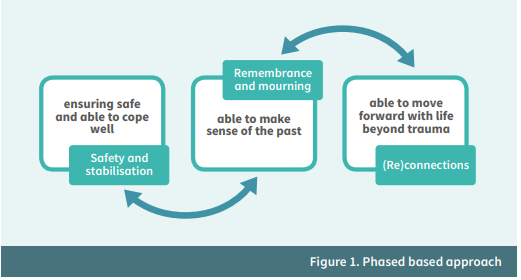

The stages of a phase-based model of trauma and recovery are as follows:

- Ensure the individual is safe and able to cope well.

- Promote physical and mental safety and encourage coping with the impact of trauma and enhancing emotional stability.

- Make sense of the past and processing the trauma.

- Focus on remembrance and mourning, helping to reduce the emotional distress linked to the memory of past trauma.

- Start to re-frame their distress in terms of general health and wellbeing, working to remove the stigma and shame around mental health.

- Move forward with life and beyond trauma.

- Enable the person to make active life choices, living a life of choice and agency.

Taken from NHS Education for Scotland’s Transforming Psychological Trauma Framework.

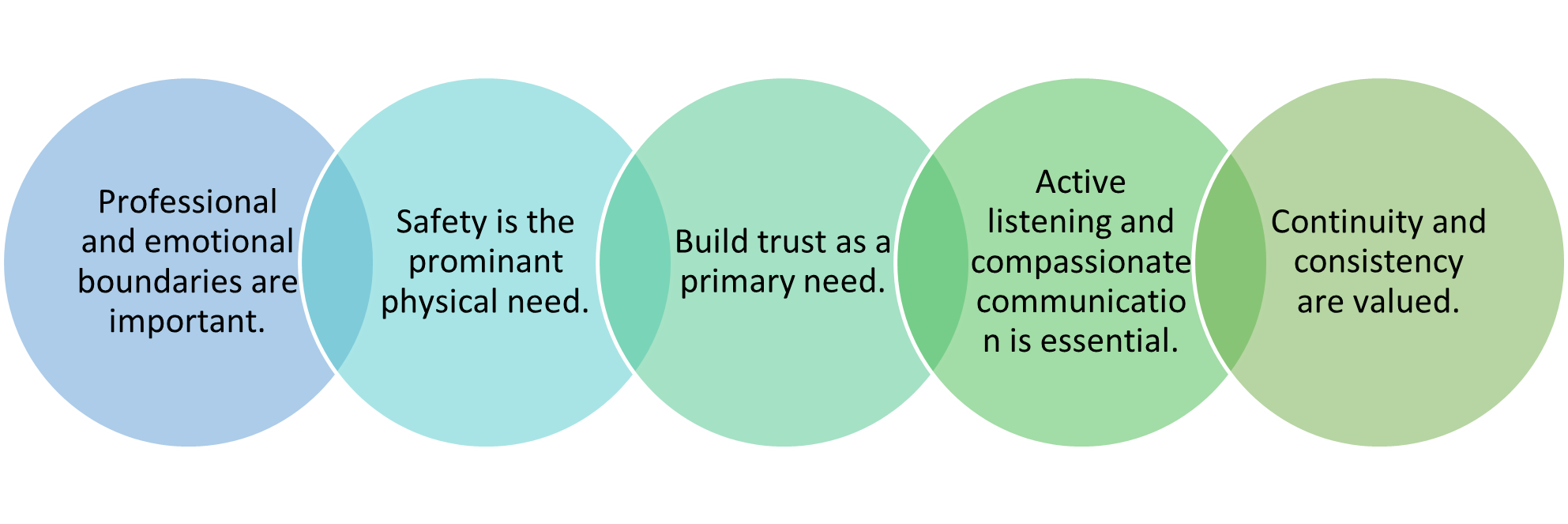

NHS Education for Scotland spoke to those affected by trauma, and found the following themes for to be aware of:

When working in a trauma-informed way, please bear in mind these themes in order to create a safe and empowering environment.

Principles for engagement with refugees and asylum seekers

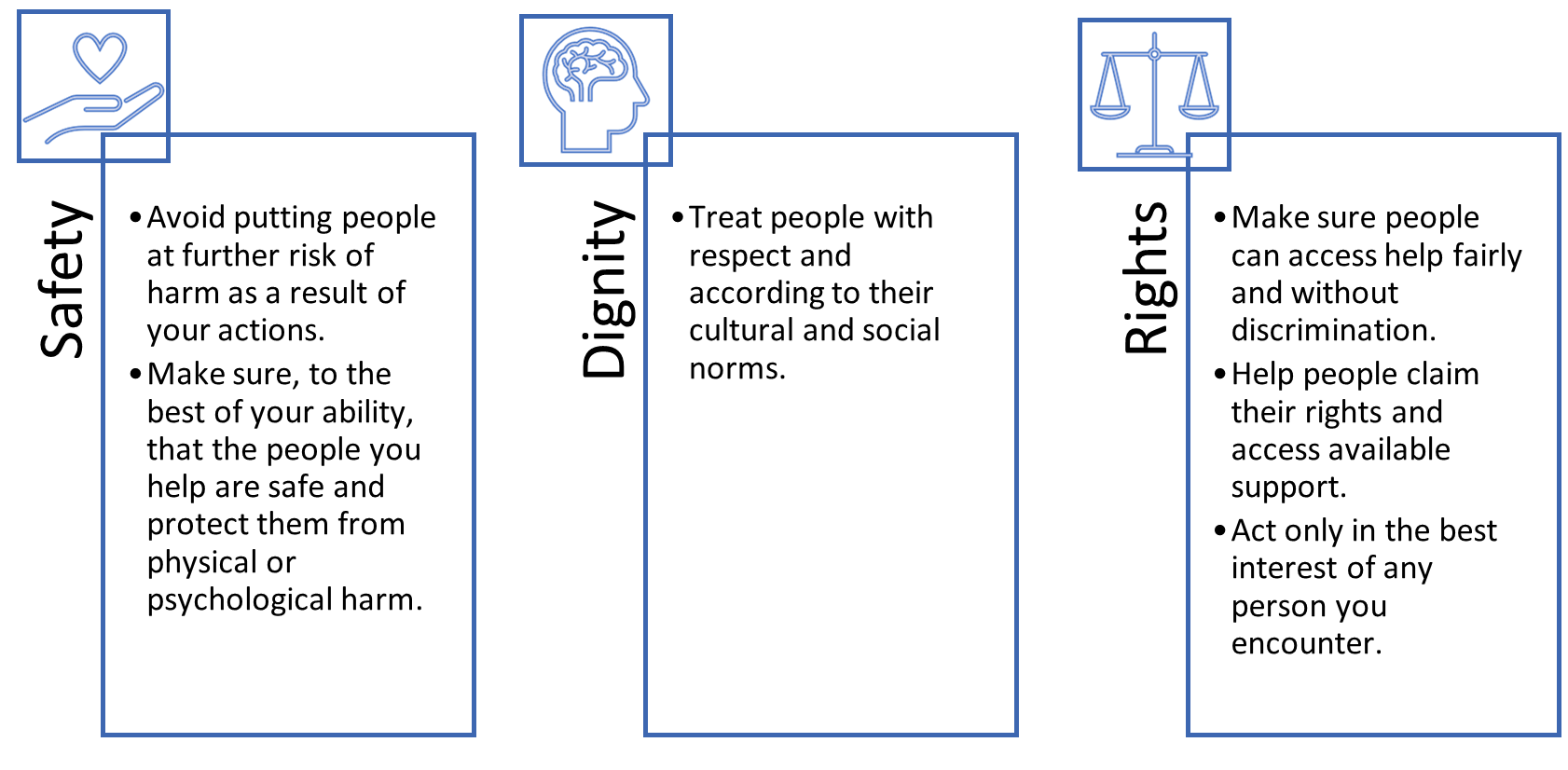

These principles are adapted from WHO guidance.

To further develop the principles for engaging with refugees and asylum-seekers in a culturally competent and trauma-informed way, these principles are adapted from the WHO guidance for ‘Mental Health and Psychosocial Support for Refugees, Asylum Seekers and Migrants on the Move in Europe’ written in 2015.

-

Treat all people with dignity and respect and support self-reliance.

- This goes alongside the principles of trauma-informed practice and is essential in all interactions. This means that you respect a person’s…

-

Respond to people in distress in a humane and supportive way.

- Utilise principles of Psychological First Aid.

-

Provide information about services, supports and legal rights and obligations.

- Utilise KCL’s directory to access community support.

- Read ‘How to assist Afghan Refugees accessing support’ section for further information.

- Refugees should feel that they have autonomy and involvement and are informed enough to make decisions in their own care.

-

Provide relevant psychoeducation and use appropriate language.

- Read ‘Supporting mental health conversations’ section.

- Ensure sufficient and appropriate translation is available, in their native dialect.

-

Prioritise protection and psychosocial support for children, in particular children who are separated, unaccompanied and with special needs.

-

Strengthen family support.

-

Identify and protect persons with specific needs.

-

Make interventions culturally relevant and ensure adequate interpretation.

- Translate resources into Pashto, Dari, and Farsi.

- Wellbeing Guidance has been translated and is available here.

- Good Thinking has published a guide on ‘5 Ways to Wellbeing & Islam’.

-

Provide treatment for people with severe mental disorders.

- Know how to refer people into NHS specialist mental health services, or to their GP.

- Utilise the Refugee Councils Therapeutic Wellbeing Resources – Refugee Council.

-

Do not start psychotherapeutic treatments that need follow up when follow up is unlikely to be possible.

-

Monitoring and managing wellbeing of staff and volunteers.

- Read ‘Looking after yourself and colleagues’ section.

-

Do not work in isolation: coordinate and cooperate with others.

Perceptions of mental health in the Afghan community

The vocabulary of mental health is very new to Afghans.

Many Afghans are not aware of the words equivalent to depression, anxiety or PTSD in Dari or Pashto. This is not to say that Afghans do not suffer from mental health problems. However, they have a different way of describing mental health problems. Many Afghans use words such as “Tashweesh” (worry), “jigar khoon” (heartbroken), “Asabi” (a description of extreme anger) and “fishar bala, fishar payeen” (in literal sense it means high and low blood pressure, but Afghans use this when hit with extreme emotions of anger or sadness). Most Afghans consider their mental health problems as a reaction to their environment, hence it is not stigmatised as such. However, conditions as epilepsy, psychosis or schizophrenia, and disabilities from birth are highly stigmatised in the Afghan community. This is because some Afghans believe that these conditions are a result of God’s punishment or have supernatural causes.

Mental distress can also be shown through violence in the Afghan community. For example, men might show their distress through violence towards the wife or children. The women might show their distress through beating themselves or their children.

Rather than discussing mental health in the same way as in the UK, Afghan’s will often verbalise their ‘Tashweesh’, or worries. These are the anxieties and worries any person may have in relation to their living situation or mental health. These are seen as a normal reaction to their circumstances, and do not hold the same stigmatisation as a conversation around ‘mental health’ would. Oftentimes, mental distress may present somatically, such as pain in the stomach, chest, or head, or troubles sleeping.

When having Tashweesh, a member of the Afghan community will often approach their family for support and guidance. In Afghan culture family is sacred. For some Afghans the extended family (grandparents, aunts/uncles, cousins) is also considered as immediate family and hold almost equal values to parents and siblings. Afghans always try to keep the problems in the family. This is why they will approach the religious/wise person of their family if they have any problems.

Afghans do not seek help in some situations. For example, if a child’s behaviour is not bringing shame or dishonour to the family, the family is not likely not seek help for the child even if the child is suffering.

If speaking within the family does not help to ease their concerns, they will approach their local religious leader for aid. Many Afghan’s rely heavily on their religion for support in times of struggle.

Supporting mental health conversations

The majority of the problems for Afghans originate from being victims to uncertainty, unpredictability, and conflict for over four decades.

For many Afghans there will be many feelings of loss and sadness about the past, and fears and anxieties towards the future. Therefore, it may be useful to help them to ground to the present moment and normalise any negative thoughts or feelings they may be having. They are reacting normally to an abnormal situation and may need support to stabilise and process the impact of the recent events.

When initiating a conversation around mental health, taking a compassionate and engaging approach is essential. You may find that utilising the ‘SIGNSS’ methodology will give you a framework for connection.

Situation – Try using a situation to find common ground. A recent, current or future event that means something to you both. It is important to remember to treat them as a human being first, and a refugee second. By taking the time to connect with the person, you will create an environment of warmth and engagement to encourage deeper conversation.

Oftentimes, asking them what they would like to be called is a good way to welcome a relationship, as it gives them agency and prevents you from making any assumptions.

Initiate – Initiating a caring conversation is an act of kindness, good for your own wellbeing as well as for someone else. A direct question, asked gently, gets to the point and is an honest way to begin.

- ‘I wanted to ask how you have been doing, how have you been managing?’

With the Afghan community specifically, here are some good questions to ask to initiate a conversation around mental health:

- ‘Are you having trouble sleeping?’

- ‘Are you worried about anything? Family?’

- ‘Are you having trouble remembering things?’

- ‘How are you coping here?’

- ‘What is your routine here? Is there anything you are unable to do that you would like to?’

Avoid any westernised language around mental health. Use ‘low mood/sadness’ rather than ‘depression’, ‘fear/worry’ rather than anxiety. Speak about mental health in terms of general health and wellbeing, reframing and normalising their distress.

Guide – Being a good listener shows someone that you are genuinely interested in how they are doing. Use open-ended questions to guide them into talking more, without judgement or negative reactions to what they have to say.

- ‘You mentioned sleeping troubles, how has that been affecting you?’

Put mental health into the context of their experience and normalise the reaction to their experience and distress.

Nudge – A nudge in the right direction can help people to search for their own resolution. Positive encouragement and practical suggestions can be a helpful prompt. One practical suggestion may be a simple grounding technique, such as breathing exercises. Perhaps encourage the following:

- Find a quiet space. You can do this exercise sitting in a chair with your feet on the ground.

- Place one hand on your chest and one hand on your stomach.

- Breathe in for four seconds, feeling your stomach rise.

- Then breathe out for four seconds while pressing gently on your stomach.

- You can repeat this as many times as you wish.

Support and Signpost – It can be hard to know where to turn and what help is available. You can use this opportunity to point someone in the right direction for support. Please see the following section for further guidance.

A member of the Afghan community that is struggling with their mental health will be much more likely to reach out to friends and family before seeking professional support, so encouraging open conversation around mental health within the family and then gentle guidance towards professional support such as GP’s will be essential.

Tips for speaking with someone distressed:

The following is taken from City of Sanctuary Mental Health Resource Pack.

- Speak slowly and calmly.

- Reconnect the person to the present by orienting the person to be here and now.

- Help him or her connect to his or her own body.

- Connect the person to the worker and safe context of the room.

- By using the five senses, direct their awareness from their past traumatic experiences to the aspects of their immediate surroundings.

- Breathing: Ask the distressed person to inhale slowly and deeply through their nose and exhale slowly through their mouth.

- ‘Listen to my voice. I am (your name), your GP/social worker/etc. You are in my office. Can you hear my voice? Nod your head if you can hear my voice.’

People who likely need special attention:

People who may be vulnerable and need special help in a crisis include:

- Children, including adolescents

- Parents and carers of young children

- People with health conditions or disabilities

- People at risk of violence

Remember that all people have resources to cope, including those who are vulnerable. Help vulnerable people to use their own coping resources and strategies.

How to assist Afghan refugees accessing support

It is important to recall and to remind all newly arrived Afghan refugees that they have a right to access free healthcare through the NHS and have the same rights to access as UK residents.

These refugee arrivals will have been granted refugee status. More information on NHS entitlements can be found in this animation.

You should ensure that refugees understand their entitlement to healthcare. It is recommended that you share with patients the NHS ‘My Right to Register’ cards as they may reduce registration refusal once the patient has been re-settled to a new local authority. (Individual Health Assessment Toolkit, PHE).

Many refugees may see going to the GP as a sign they are abnormal. It is important to communicate that the GP is a non-judgemental professional that just wants to help, and that it is completely normal to go and see your GP when you are having mental distress.

When encouraging refugees to seek help, it is important to involve them fully in their own care. In partnership with City University London, the Refugee Council have developed practical resources to support refugees and asylum seekers in accessing primary healthcare. These include a guide to using the GP, a communication card with useful vocabulary and phrases with translations, and introduction card to request fair and compassionate treatment, and a poster which maps out the different NHS services.

These resources have also been translated in Dari and Farsi.

Broader wellbeing and integration into UK society is an important factor in improving the health and wellbeing of new migrants. This is particularly important for children, for whom social interactions and play form a critical part of their happiness and development.

Asylum seeker and refugee pupils aged 5-18 have exactly the same entitlement to full-time education or training as other pupils in England and economic migrants. This rule applies equally across local authority schools, academies, and free schools. Please help to support children to attend full-time education.

Signposting patients and families to other support services should also be considered, including but not limited to:

- English as a second language classes

- Local food banks and voucher schemes

- Adult education centres

- Children’s centres

- Local clubs and activities

Please use the Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) Directory for Refugees and Migrants in London, produced by the Centre for Society of Mental Health at Kings College London, to signpost Afghan Refugees to relevant community organisations that will host many of these activities.

Looking after yourself and colleagues

This is a hugely challenging time for professionals and volunteers supporting the Afghan community.

Even if you are not directly involved, you may be affected by what you see or hear while helping. As someone providing psychosocial support, it is important to pay extra attention to your own wellbeing. Take care of yourself, so you can best take care of others.

The following suggestions may be helpful in managing your stress:

- Think about what has helped you cope in the past and what you can do to stay strong.

- Try to take time to eat, rest, and relax, even for short periods of time.

- Try to keep to reasonable working hours so you do not become too exhausted and experience burn out, which can lead to dissatisfaction at work and sometimes compassion fatigue.

- Consider dividing the workload across a team, working in shifts during the acute phase of the crisis and taking regular rest periods.

- You may feel inadequate or frustrated when you cannot help people with all of their problems. Remember that you are not responsible for solving all of people’s problems. Do what you can to help people help themselves.

- Minimise your intake of alcohol, caffeine, or nicotine.

- Check in with those around you to see how they are doing and have them check in with you. Find ways to support each other.

- Talk with friends, loved ones, or other people you trust for support.

Taking time for rest and reflection is an important part of your helping role.

- Talk about your experience of supporting with a supervisor, colleague, or someone else you trust.

- Acknowledge what you were able to do to help others, even in small ways.

- Learn to reflect on and accept what you did well, what did not go very well, and the limits of what you could do in the circumstances.

If you find yourself with upsetting thoughts or memories about your work, feel very nervous or extremely sad, have trouble sleeping, or drink a lot of alcohol or take drugs, it is important to get support from someone you trust. Speak to a health care professional or, if available, a mental health specialist if these difficulties continue for more than one month.

Further resources

Here are just some of the resources to aid professionals in supporting the Afghan Refugee community.

This list is by no means extensive and is meant to serve as a starting point:

- Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) Directory for Refugees and Migrants in London. Produced by the Centre for Society of Mental Health at King’s College London.

- Moments for Mindfulness. A self-help guide to managing stress and uncertainty by the Refugee Council.

- Resources to support refugees and asylum seekers in accessing and understanding the NHS.

- A trauma workbook developed by Good Thinking to help those who have experienced trauma to process their emotions and begin to heal.

- Further coping mechanisms for stress by Good Thinking.

- City of Sanctuary’s Mental Health Resource Pack aimed towards professionals working with refugees and asylum seekers.